Citi's Willem Buiter sums it all up: "...the improvement in sentiment appears to have *long overshot its fundamental basis* and was driven in part by unrealistic policy and growth expectations, an abundance of liquidity and an increasingly frantic search for yield. The key word in the recovery globally, and in particular in Europe, growth is *fragile*. To us the key word about the post summer 2012 Euro Area asset boom is that *most of it is a bubble, and one which will burst at a time of its own choosing*, even though we concede that ample liquidity can often keep bubbles afloat for a long time." His conclusion is self-evident, "markets materially underestimate these risks," and the post-Draghi european performance has "gone well beyond the point of possible self-validation and therefore looks fragile."

Citi's Willem Buiter sums it all up: "...the improvement in sentiment appears to have *long overshot its fundamental basis* and was driven in part by unrealistic policy and growth expectations, an abundance of liquidity and an increasingly frantic search for yield. The key word in the recovery globally, and in particular in Europe, growth is *fragile*. To us the key word about the post summer 2012 Euro Area asset boom is that *most of it is a bubble, and one which will burst at a time of its own choosing*, even though we concede that ample liquidity can often keep bubbles afloat for a long time." His conclusion is self-evident, "markets materially underestimate these risks," and the post-Draghi european performance has "gone well beyond the point of possible self-validation and therefore looks fragile."Excerpted from 'New and Old Risks in the Euro Area', Citi's Willem Buiter

Then Buiter rips apart the Central Banker's meme of *'markets' as policy tools..*.

We recognise that, in a decentralised market economy where expectations of the future, moods, hopes and fears drive private (and sometimes also government) behaviour directly and *through their effect on the prices of real and financial assets, today’s subjective expectations and other psychological characteristics in part determine what tomorrow’s fundamentals will be*.

Irreversible or costly-to-reverse decisions like capital expenditure, human capital formation, resource extraction etc, are driven by subjective expectations and moods, making the *distinction between a fundamentally warranted asset boom and a bubble slightly fuzzy at the edges*.

*But this indeterminacy*, bootstrapping, self-validating characteristic of complex dynamic economic systems inhabited by partially forward-looking households, firms and policy makers – called reflexivity by George Soros – *can be taken too far*.

Mere optimism and confidence will not permit the authors of this note to bootstrap themselves into winning the men’s doubles at Wimbledon 2013. The fact that financial markets have radically reduced their implied estimates of the likelihood of sovereign default in the periphery of the EA (other than in Greece) and of senior unsecured bank debt restructuring throughout the EA, core as well as periphery, should not stop us from continuing to analyse carefully the fundamental drivers of both sovereign credit risk and senior unsecured bank debt credit risk. When we do this, *the conclusion that the markets materially underestimate these risks is, in our view, unavoidable*.

Eliminating or mitigating some risks of disaster does not create an engine for sustained growth...

Let us *recall the major headwinds for the world economy and Europe in particular*. Private sector debt has hardly fallen in many EA countries to date and remains much above the levels at the beginning of the last decade (Figure 4).

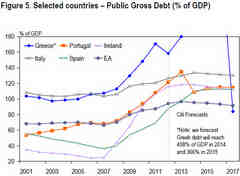

Fiscal deficits have fallen in most EA countries, but general government gross debt continues to rise and remain close to all-time highs outside of war periods for many advanced economies (AEs, Figure 5).

Continued fiscal austerity thus remains all but certain in many AEs.

Many banks (both in the core and the periphery of the EA) remain weak despite a substantial amount of operational restructuring and selective recapitalizations and deleveraging. In many EA and in a number of non-EA member states of the EU, the entire national banking systems remain weak, fragile and unable or unwilling to provide funding to the real economy on a scale sufficient to support a sustained recovery.

The path to economic recovery, let alone sustained growth at an attractive growth rate of potential output remains an arduous and long one.

Euro area policy actions or announcements have also been misinterpreted or at best over-interpreted.

The *ECB now provides a selective safety net* for the banking sector through the LTROs (ring-fencing banking activity against a systemic collapse) and through the OMT. The OMT ring-fences sovereigns against convertibility or break-up risk, but not against the risk of sovereign debt restructuring through official sector involvement, OSI, through concessions by official creditors, or through private sector involvement, PSI, through concessions by private creditors. These measures effectively rule out the key tail risk of a break-up of the Eurozone through an involuntary forced exit of the fiscally and competitively weak member states.

It is key to recognise the fact that *neither the ECB nor the ESM, nor any foreseeable evolution in their scope and resources, eliminate the risk of bail-in of unsecured bank creditors* (including senior unsecured creditors, up to unsecured bank bondholders and non-guaranteed/uninsured depositors) in Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Slovenia and indeed, unless the sovereigns in the core really are willing and able to open their pockets to support their own banks’ unsecured creditors, in Belgium, France, the Netherlands and Germany.

In addition, a number of risks have in fact increased recently.

*1) Political risks in Italy and Spain*

*First, there are renewed political risks.* In Italy, the Monte dei Paschi di Siena (MPS) bail-out is providing further support to the growing momentum former PM Berlusconi‘s party enjoys in the most recent polls, raising risks of a hung parliament in the upcoming election on February 24. The fact that *ECB President Draghi was Governor of the Bank of Italy at the time when it was the supervisor of MPS* when MPS is alleged to have engaged in a number of dubious financial operations creates the risk of reputational damage for the ECB President.

More significant than the individual reputations at risk is the risk that the MPS issue reinforces concerns about the potential for reputational damage to the ECB once it takes on the role of the main EA bank supervisor under the new Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), a concern voiced in general (rather than specific to the MPS issue) by ECB Executive Board Member Constancio recently.

*Even before the MPS issue, the near-term prospects for further near-progress on banking union were dimmed by two other factors.* First, the German general election, due to be held in September 2013, has reduced Chancellor Merkel’s appetite for policy actions that could be controversial domestically. This might preclude any major concessions to Germany’s EA neighbours as regards the timing and phasing of fiscal austerity, and the early introduction of key elements of banking union.

*Meanwhile, in Spain, allegations about financial malpractice in the ruling Partido Popular party have further hurt the party’s popularity.* They are likely to limit government effectiveness in taking unpopular further reform measures and have increased – otherwise modest – risks of government instability, should these allegations be found to be true.

*These developments will in particular make it harder for the Spanish government to impose substantial additional fiscal austerity.* Additional fiscal tightening would be needed to meet deficit targets following a likely diagnosis of deficit overshoots in the spring. This is despite the new, softer (and IMF-induced) conventional wisdom towards fiscal tightening in response to deficit overshoots: make up bad faith deficit overshoots within the original time frame but permit bad luck deficit overshoots to be corrected over a longer horizon. *Unless there is a Keynesian Laffer curve (fiscal tightening depresses activity to such an extent that the deficit increases) the new conventional wisdom will raise the risk of future debt unsustainability.*

*In Greece*, the government announced a primary surplus for 2012 on the basis of preliminary budget figures, but government officials also noted that the final figure is likely to be revised to a *deficit of 1.2-1.3% of GDP*. The *domestic political situation remains tense*, as evidenced by the civil mobilization orders that the Greek government has issued to metro and maritime workers. Political tensions and the risk of political instability translate in a direct and somewhat disconcerting manner into economic and financial uncertainty, the likelihood of an earlier recourse to further sovereign debt restructuring and the risk of dysfunctional politics leading to Grexit.

*2) Excessive contagious optimism among policymakers*

*Second, the rally in asset prices and in particular the reduction in funding stress for both sovereigns and banks in the EA periphery has also lessened the perception of many policymakers of the need for major further support measures in the near-term, a perception that is evident by various remarks to the effect that ‘the worst of the crisis is over’* (see e.g. Euro Area: Sovereign Debt Crisis Update 23 Jan 2013).

Notably, ECB President Draghi neglected these dynamics when he spoke of ‘positive contagion’ at the last ECB policy meeting. In our view, there is no such thing as ‘positive contagion’ if the term ‘positive’ refers to the real economic impact of the contagion. Excessive contagious optimism, detached from fundamentals, usually ends up hurting more than it helps, even though the improvement in financial conditions that resulted from the recent rally has probably eased some of the pain in fiscally and financially weak EA countries.

*3) Bail-ins of bank creditors (junior and senior) are undoubtedly coming closer*.

The combination of the likely further capital needs of EA banks, the limited financial resources of the EA sovereigns (even in the core) and political opposition to bailing in tax payers to avoid bailing in senior unsecured bond creditors make it likely that bail-ins of senior unsecured bank creditors in the EA will start before 2015.

The economic and financial risks facing the EA are not only driven by governments and politics.

*4) The recent appreciation of the euro and the effective monetary tightening *implied by the increase in money market rates (driven by the large repayments of the first 3Y-LTRO on Jan 30) are most unwelcome from the point of view of EA domestic demand.

Summing up, in our view, the EA sovereign debt and banking crisis is far from over. If anything, recent developments, notably policy complacency bred by market complacency, combined with higher political risks in a number of EA countries *highlight the risks of sovereign debt restructuring and bank debt restructuring in the EA down the line.*

Source: Citi Reported by Zero Hedge 2 days ago.